SOUQ

During the summer of 1968, at age eight and a half, along with my six-year-old brother, Dennis, and Mom, we reunite with

“Guys, let’s go downtown to the souq (market) today,”

Driving toward the souq in the intense morning heat, there is already a hotbed of activity.

“Wow, this is wild,” Mom shouts.

Men in white traditional thobes (a loose, white garment covering the whole body, down to the ankle) ride on mopeds and bicycles, buzzing alongside new and old American cars from the ‘60s. I constantly hear horns honking. A man in his traditional white thobe, flip-flops, and taqiyah sits sideways, steering his donkey-drawn wooden cart as he slowly passes by the cars. The taqiyah is a small white cap that keeps the ghutrah from slipping off the head. The ghutrah is usually of white cotton cloth, but many have a checkered pattern in red or black stitched into them. The agal is a doubled black cord that is used to secure the ghutrah in place. The bisht is the loose robe worn on top of the thobe by Arab men. They are often black and trimmed with beautiful golden embroidery.

Burns/Souq/Page 2

White and red ornamental flowers budding out of tall, green bushes, date palms, and green trees of various sizes decorate the road. Various shades of white or beige three-, four-, and five-story mud/stone houses—maybe higher—rise above the city. Some of them are falling apart, as a corner of the sidewall is in rubbles, but the rest of the house appears maintained. I wonder if anyone lives here, I think to myself.

Turquoise, various shades of green, dark-brown or bleached wood-colored overhanging balconies have a lacelike appearance, covering half a facade or an entire floor. Intricately carved wooden top and base panels appear crocheted. Occasionally windows are open, although we cannot see inside. At times, arched or square doorways are made of ornately carved wood painted blue or light green adorning the entrance. Continuing alongside a black-and-white-checkered curbstone, tall, thin-stemmed, round green shrubs, suddenly, a vanilla-white four-story stone building appears majestically in front of us. Coronet points—also in vanilla white—similar to the queen piece in chess beautify the roof. Around the roof’s trim a series of raised, white oval designs envelop two small circles next to each other with a dark center. They look like eyes. Dark-chocolate-colored overhanging balconies of meticulously carved and embossed wood embellish the middle of the building from top to bottom. Fourteen, tall arched-shaped windows with closed shutters of a vertical crocheted like design in a dark-chocolate color garnish each facade. Vanilla- white columns with a gold trim separate each set of windows. The house reminds me of the birthday cakes displayed in the Italian bakery back home.

Burns/Souq/Page 3

As

We begin our long walk down the dirt road, careful not to step into a crack or pothole. Banks with signs in English and Arabic hang next to the building’s facade. Pepsi and Coca-Cola billboards are everywhere. Sometimes the Pepsi sign is a picture of a red, white, and blue bottle cap with a blue “PEPSI” in the center. Another sign is next to it, but in the center is black Arabic writing with a white “PEPSI” encased in a red-and-blue icon. Men in traditional clothes stroll casually wearing either sandals or flip-flops. Sometimes they wear a dark-gray thobe, a light-colored shirt, and pair of pants or a black suit with a white shirt. There is no flow of traffic except for an infrequent car or truck outside a shop. Amidst the hustle and bustle, passersby clog narrow alleyways, examining the wares, socializing, or just strolling to take in what to buy. Above some of the shops is a small, sand-colored house with open turquoise shutters above small porches.

Suddenly, a three-tier white minaret with two circular porches, narrow windows, and a conical top rises above the city. Throughout the day, I hear a man’s voice calling from the top of the minaret: “Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar.” “God is the greatest, “

“A Muslim is called to prayer five times a day (salat). The call to prayer is heard at dawn, at

Burns/Souq/Page 4

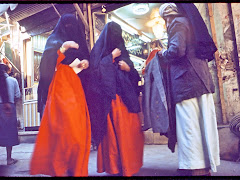

In spite of the heat and flies everywhere, people go about their lives. Saudi women gracefully move about, fully covered in their black abayas—a long-sleeved, floor-length, loose garment worn over other clothing when a woman leaves the protection of home. The abaya covers the whole body except the face, feet, and hands. It can be worn with the niqab, a face veil covering all but the eyes. I do not see any part of the body as they glide through the streets resembling moving dolls. Some carry a stuffed blanket perched on their heads. Large and small round flat, Arabic bread neatly stacked as pancakes lie on glass shelves behind windowpanes in the stalls below houses. I often notice rows of two to ten bananas bunched up, dangling on string from a metal rod. Below round tin trays hold pyramid-shaped mounds of a variety of dried fruits, nuts, and spices—most of them I have never seen before. Sometimes wooden benches or cardboard boxes support the mounds of lemons and oranges, which lay one on top of one another in neat rows above the street.

“I want a Coca Cola,” says Dennis. “Let’s continue along the souq first, Mom replies.

“

“Never. If you do, your hand is chopped off.”

Watermelons piled on top of one another lay in heaps on the sidewalk, resembling white and green soccer balls. I hear a man calling, “American, please, you look,” as he slices the watermelon in half, offering Dennis and me a wedge. The taste of sweet water soothes me in this heat.

Burns/Souq/Page 5

We pass stalls with glass containers of sizzling, crispy chickens rotating on skewers. They make me hungry. The aromatic smell of roasting chicken reminds us to buy a few for dinner. A boy holding a large straw basket over his shoulders approaches

“The basket boy wants to make a few riyal offering to carry our items. If we need help finding something, he will direct us,”

“Great,” we all chorused.

He places our watermelon into the large straw basket. Lifting it up off the ground over his shoulders, an indent on the bottom protrudes inward toward the top of the basket as he places his head snugly underneath. Tightly woven rows of straw surround it with a raised rim at the top. Our basket boy stands tall with his red-and-white checkered ghutrah over his taqiyah and glides gracefully across the dirt road. His left hand hangs comfortably at his side. With his right elbow bent, he raises his hand while his thumb and four lifted fingers support the bottom of the basket—effortlessly balancing it. He wears a regular butterscotch-colored short-sleeved shirt over a black-and-white-checkered skirt wrapped around his waist and flip-flops on his dark-skinned feet. He faithfully follows us as he utters an occasional “As-Salamu Alaykum” aloud. “What is he saying,

“Hello.”

“Stay close to me, Carina!” Mom mentions.

As I hear Arabic spoken, it sounds heavy and strange—completely different from English. At the end of the road, we enter the main souq, with a covering, overhead protecting us from the sun. As if the genie uncorked his magic lamp and whisked us away to another world on

Burns/Souq/Page 6

his magic carpet. Walking along a narrow concrete or dirt road with cracks and holes, my armpits are moist with sweat. I am constantly waving away the flies as strange smells fill the air—a blend of everything spicy.

Holes in the wall on both sides of the street sell anything you desire. We walk zigzag sometimes through open-air alleys, with the hot sun beaming down on us. Similar to the expression “a hole in the wall,” I get to experience the expression firsthand, understanding its true meaning. Souq are winding alleyways lined with shops or, literally, holes in a wall, selling pots and pans, gold, clothes, fabric, footwear, shirts, toys—everything you need is available in the souq. If you wanted to buy gold, you would go to the gold souq. If you wanted to buy fabric, you go to the fabric souq and so on. Owners would try to get you to step into their shop but wouldn’t harass you if you go next door—although sometimes they lured you into their shop with a cup of shy (a sweet mint tea).

Amidst the huge maze of souqs are smaller souqs of illuminated alleyways of exotic spices and smells—namely incense and cardamom. Six tin buckets filled with colorful mounds of spices sit atop wooden crates against a hole in the wall. They sting my nose. Red-and-blue-coiled hubbly-bubblies (water pipes for smoking) hang from nails high above various-sized boxes of tobacco. Up to now I see only men selling goods. Four women—young and old—wear dresses covering their arms and legs and straw hats over white shawls wrapped around their heads exposing their faces. Sitting in flip-flops, next to round tin pans

Burns/Souq/Page 7

propped on boxes, they sell small round, flat bread. In the stall near the spices is a fan-shaped white scale.

“You and Carina need to choose material for your thobes.”

“Our what?” Mom and I ask. “That is the word for the long dresses you will need to wear. Guys, here is the fabric souq.”

A man sits behind a desk hidden in the back of the stall among every color and pattern imaginable. Rolls of fabric tightly wrapped around wooden rods are set next to, behind, and on top of one another filling up the entire hole in the wall. Mom points to the cotton fabric of blue, yellow, gold, orange, and white in a flower pattern. Picking up the rod of material, he unfolds it against the measuring stick under the glass countertop. He then unfolds the material five more times around his arm. When he finishes he cuts the fabric once with scissors and sets it aside. I point to the pink, yellow, orange daisy pattern made of cotton. The man yanks the rod tucked behind the others and places it on the glass counter. Speaking in Arabic, he measures and wraps our material in brown paper.

Burns/Souq/Page 8

“Are those men in beige uniforms with thick, white belts and greenish flat hats policemen?”

Dennis inquires.

“Yes. Some are religious police—muttawa. They often carry sticks to click a person’s heels, reminding them to pray.”

“Everyone barters here, Du. Never accept the price they offer. It is normal to barter,”

My favorite stall is the illuminated gold jewelry stall.

“Joe, Carina and I are going to look at the jewelry.”

“Okay, Dennis and I will look at the watches here next to you.”

Gold and silver necklaces hang neatly under a glass countertop beaming in the sunlight. Silver necklaces—crescent- or square-shaped with beads—dangle underneath. Gold bracelets resembling large gold coins are stacked up high underneath the glass. So much gold glistens and blinds me that I do not know where to begin. Sitting behind the counter, a man yells in broken English to Mom and me, “Please, you come in.” Amazed, we step inside, looking at the glass countertop. Holding a thick gold bracelet, the man hands it to me to try on. I am not sure if I want to buy this one. Suddenly, on the bottom shelf, an elegant gold snake ring surrounded by green enamel and a cluster of ten tiny ruby stones mounted on a gold rim for its head and two rubies for the eyes intrigues me. I try it on my pinky carefully so that it does not become stuck.

“

Burns/Souq/Page 9

“Du, are you interested in this one?”

“I think so. I might even buy two.”

He also sells Bedouin jewelry over here.

Mom wears her two gold bracelets as I wear my snake ring, watching the rubies glisten in the sunlight. The man wraps the silver necklace and hands

Burns/Souq/Page 10

shoes laid out on rugs hang over the edge of the curb onto the dirty street. Across the alleyway, separate from the women, men’s and boys’ clothes hang on hangers suspended from a wooden stick nailed into the concrete walls outside the stalls. Among the bright-colored clothes, small red, blue, and orange rugs hang folded over a wooden rod. A small tilted box of nectarines lay on its side above the larger tilted box of oranges. A mound of lemons sits on a tin tray underneath a bunch of bananas hanging on string.

Men yell at us, “Please shy,” inviting you to drink and buy. Arabs are kind and helpful and enjoy bartering with

Away from the covered souq, along a sandy road with loose brick rubbles, a woman in her black abaya showing a bit of red-and-black dress carries remnants of a green bush on her head and a small white lamb in her left hand. A man in his white thobe supports some type of skinned animal over his shoulders. In the open-air market, across from the display of watermelons, four-foot mounds of chestnut- or grayish-white-colored coiled wool lie on the dirt road. Fruit, lettuce,

Burns/Souq/Page 11

potatoes, carrots, onions, grains, vegetables, etc. lie exposed under the sun upon straw mats, under umbrellas, or on a wooden tray. Some vegetables I do not recognize. It is common to see a saddled camel with ten or more gracefully moving along the dirt road. Two camels lie next to the house under a handmade canopy of canvas and wooden beams, with a round tin bucket of water supported by a small pyramid of bricks.

We arrive at the tailor’s house. Ringing the doorbell, we hear “As-Salamu Alaykum.” We climb a steep set of stairs to the top entrance as a woman answers the door wearing a skirt and blouse. She escorts Mom and me into a hot room with rolls of fabric everywhere. The sewing machine is near the only window and fan, offering an occasional breeze from the sweltering heat. This delightful woman using hand gestures to communicate measures us. We hand her our package of fabric. She wraps us in our material from our neck down to below the ankles, making a bottom hem. She then wraps material around our arms as sleeves down to our wrists. She offers us shy.

Mom and I each drink a glass. The tailor gestures us raising five fingers and in broken English, says, “You come back khamsa days.”

We meet

Smiling and graciously opening his hand to accept three riyal, our basket boy yells, “Shukran, masalama.”

A week later we return for our thobes. Mom carefully tries on her new thobes one last time for safe measure. It has to cover us below the elbow and below the knee (no limbs can show), right down below the ankle. Once Mom appeared, I stepped behind the curtain, trying on my two

Burns/Souq/Page 12

new thobes. She then tightly packs our purchases in brown paper. Mom hands her about 50 riyal for all four.

Whenever we see huge watermelons sitting on the side of the hot asphalt for sale, we stop and pay the watermelon boy three riyal.

thin spout into small, clear glasses. They also serve gahwah—coffee—in big or small brass pots. We often see men smoking from a mouthpiece attached to a long blue-and-red coil connecting to a beautiful ornate silver or brass stand.

Again,

Geckos are everywhere. I frequently see them climbing up walls or staring at you ever so still, glued to the surface. It is extremely hard to catch them, as they are quick and nimble. When we returned to the villa after a fun-filled, hot day at the souq, Dennis and I reminded

“Did I say that?”

Burns/Souq/Page 13

“Come on

Dinner consists of roasted chickens, salad that still had the remnants of the Clorox Mom used to clean the leaves, cucumber salad, watermelon, and big Arabic bread rounds. We brought the cots onto the open-air roof and slept under the Milky Way in the coolness of the night.

THE END

No comments:

Post a Comment